Jay Griffiths is an author with an unlikely, but impressive, fan base: rock stars.

Musician KT Tunstall quoted from Griffiths' book Wild: An Elemental Journey on the cover for her album Tiger Suit, while Nikolai Fraiture from The Strokes has said, "Jay Griffiths’ works are original, inspiring and dare you to search beyond the accepted norm."

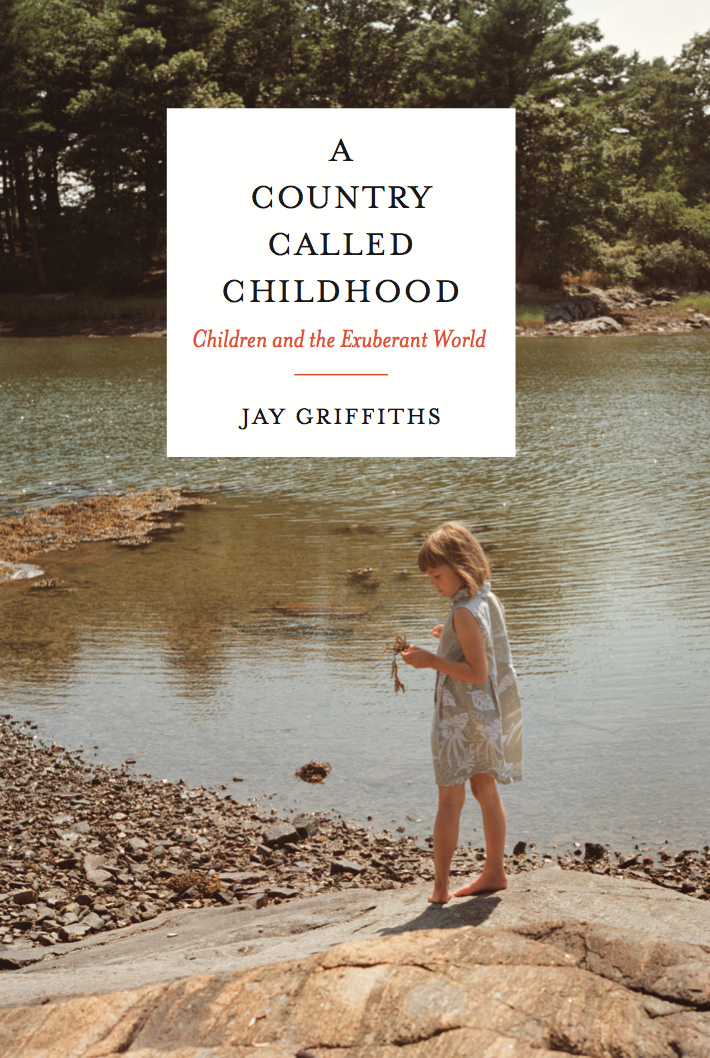

The British writer and author of Pip Pip: A Sideways Look at Time and Love Letter from a Stray Moon was the winner of the inaugural Orion Book Award and the Barnes & Noble Discover Award for the best nonfiction writer to be published in the U.S. Her forthcoming book, A Country Called Childhood: Children and the Exuberant World, explores the value of the natural world in answering these questions: “Why are so many children in Euro-American cultures unhappy? Why is it that children in many traditional cultures seem happier, fluent in their child-nature?”

Here, we provide a sneak peek of the book, set to debut Nov. 11. Order a copy here.

***

Stumbling on a bird's nest as a child, I was breathtaken. I gasped at the tenderness of it, the downy feathers, softer than my fingers, moss folded into grasses and twigs in rounds. My eyes circled and circled it, caught by the mesmerizing perfection of the nest. It was the shape of my dream, to be tucked inside a nest and to know it for home.

A nest is a circle of infinite intimacy, a field-hearth or hedge-hearth. Every nest whispers 'home', whether you speak English, Spanish, Wren or Robin. Part of a child's world-nesting need is answered seeing a rabbit warren, a badger sett or otter holt, as children's writers instinctively know, giving children a secret passage to dens, nests and burrows.

Through nests, a child's own hearthness is deepened and the child grows outwardly and inwardly into its world. Outwardly, children stare at a nest, fascinated. Inwardly, the nest reflects not just the body's home but the mind's. In the snug refuge of the nest, the psyche fills itself out from within, as round and endless as a nest, creating its infinite-thoughted worlds. Intertwined with the world of fur and feather is the world of metaphor where mind makes its nests. Metaphor weaves 'grass' and 'shelter' together. It ties 'twig' to 'refuge.' It knits 'moss' to 'home.'

Finding a nest is a homecoming for a child. In Greek, homecoming is nostos, the root of the word 'nostalgia'—an ache for home, a longing for belonging. Children, filthy little Romantics that they are, have an uncanny gift for nostalgia in nature; something inchoate, yes, but yearning, yearning for their deepest dwelling.

Every generation of children instinctively nests itself in nature, no matter how tiny a scrap of it they can grasp. In a tale of one city child, the poet Audre Lorde remembers picking tufts of grass which crept up through the cracks in paving stones in New York City and giving them as bouquets to her mother. It is a tale of two necessities. The grass must grow, no matter the concrete suppressing it. The child must find her way to the green, no matter the edifice which would crush it.

The Maori word for placenta is the same as the word for land, so at birth the placenta is buried, put back in the mothering earth. A Hindu baby may receive the sun-showing rite surya-darsana when, with conch-shells ringing to the skies, the child is introduced to the sun. A newborn child of the Tonga people 'meets' the moon, dipped in the ocean of Kosi Bay in KwaZulu-Natal. Among some of the tribes of India, the qualities of different aspects of nature are invoked to bless the child, so he or she may have the characteristics of earth, sky and wind, of birds and animals, right down to the earthworm. Nothing is unbelonging to the child.

'My oldest childhood memories have the flavor of the earth,' wrote Federico García Lorca. In the traditions of the Australian deserts, even from its time in the womb, the baby is catscradled in kinship with the world. Born into a sandy hollow, it is cleaned with sand and 'smoked' by fire, and everything—insects, birds, plants and animals—is named to the child, who is told not only what everything is called but also the relationship between the child and each creature. Story and song weave the child into the subtle world of the Dreaming, the nested knowledge of how the child belongs. The threads which tie a child to the land include its conception site and the significant places of the Dreaming inherited through its parents. Introduced to creatures and land-features as to relations, the child is folded into the land, wrapped into country, and the stories press on the child's mind like the making of felt—soft and often—storytelling until the feeling of the story of the country is impressed into the landscape of the child's mind.

That the juggernaut of ants belongs to a child, belligerently following its own trail. That the twitch of an animal's tail is part of a child's own tale or storyline, once and now again. That on the papery bark of a tree may be written the songline of a child's name. That the prickles of a thornbush may have dynamic relevance to conscience. That a damp hollow by a riverbank is not an occasional place to visit but a permanent part of who you are. This is the beginning of belonging, the beginning of love.

***

Stay tuned for more exclusive excerpts, and read our sneak peeks of other female-penned books here.